The following post is about ambivalence and remembrance. It is comprised of unstructured vignettes, loosely tied with my thoughts on identity, family, and cultural legacy. These thoughts were inspired by the fact that today is April 24, and we are 100 years removed from the beginnings of the Armenian Genocide.

I am not an authority on the Armenian Genocide. I can only speak from my perspective as a fourth-generation descendant of someone who lived through it. There are numerous scholarly, pop, and fiction texts on the subject, as well as recent media coverage of the history and current issues surrounding remembrance. I encourage you to read widely.

Here we are.

A century removed from the dawn of a genocide that massacred individuals, stolen family legacies, and endangered an entire culture.

Here we are. Here. Now.

We are.

We are, still.

The nation-state of Turkey does not publicly refer to the atrocities the Ottoman Empire committed against its Armenian citizens as genocide. It is public knowledge that this is a HUGE bone of contention for many Armenians & Armenian-Americans, and a sticking point in geopolitics. You may have read about it or heard about it in recent days on the news. I am glad this is getting media attention.

But I have come to realize that I don’t need a government to legitimize my great-grandmother’s lived experience and its continued effects on our family. That being said, I respect that many do need this, and I understand why they do. Recognition, admission of ancestral wrongdoing, is critical to healing. It gives a lot of power over the truth to governments, but that is the world we live in.

The thing that struck me about The Bastard of Istanbul (a novel whose disturbing reveal you can, to your mounting horror, see coming a mile of alternating-perspective chapters away) is that some modern-day citizens of Turkey might not know about this part of Ottoman-Armenian history, and thus have no simmering feelings or opinions about it. In this particular novel, when Turkish characters hear the story of an Armenian character’s ancestors, they are horrified and sympathetic. But this is the first they are hearing about what was a systematic eradication of an ethnic/cultural group.

Their ignorance shrouds truth. Their ignorance leaves no place for Turkish denial, for Armenian insistence, for indigence or entrenchment on either side. This ignorance is the fault of the state, not the individual. So it is the nation-state, not its people, that become the important players in the geopolitical and ethnic and cultural narrative. This politico-narrative reality is why so many Armenian-Americans are disappointed–if not angry–with President Obama, and thrilled with Pope Francis.

The Brand Library in Glendale has been hosting events, exhibitions, conversations, film screenings, for months now to mark the 100th year of survival. Several times I have been compelled enough, felt enough of a sense of duty, to put these in my calendar. Each time I did not go.

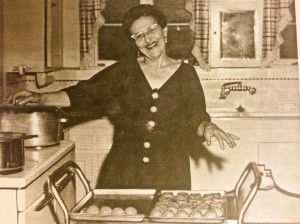

My great grandmother’s name is Vartouhi. Her story is not unique. I will probably get some details wrong, even in this brief sketch. She fled from Turkey to America by way of marrying an Assyrian whose family was harboring her. She had managed to smuggle Uncle Arto (dressed as a girl), and Auntie Bergie, who she pretended was her daughter. Their parents had been killed as they watched. Too many children could say this by 1920. Too many children can say this now. Once in Washington Heights, an older brother and extended family awaited them and they made a new life. My great-grandmother had two children, worked, divorced, sent her son to war and her daughter to work and got her son back and eventually they all moved to the San Gabriel Valley to start yet another life. Lives. Our family branched and grew. Vartouhi had escaped genocide and created a legacy.

In the early 1990’s, she sat in one of her favorite chairs in her sunny Pasadena living room and her son video taped her story. I have seen it just once, a few years back. It was strange and wonderful, to see her as I remember her at eight. To hear her voice. She and her story and its transmission and retelling and reinterpretation by my grandmother & mother are the reasons I became politicized around my Armenian identity when I was younger. That she and my grandmother are gone have lessened the immediacy of our family’s past, and have made it easier for me to become alienated from this identity over the years.

My grandmother helped me share our family heritage in 5th grade–it must have been some sort of Grandparents Day or Immigration Celebration or something similarly and singularly Elementary School. We held up a scroll of the Armenian alphabet, unwrapped my grandfather’s Christening gown, and we must have talked about things, as well. Maybe this was the beginning of my blossoming pride. In my early teens, I claimed Armenian identity in earnest. It made me special. If I had lived in Glendale or near Washington Blvd in Pasadena, it would have been less special, but maybe I would have participated in the diaspora community and be able to feel legitimate about claims to an Armenian identity today.

At 13, I had grand aspirations of learn in to speak the language. I could have–my grandmother was still alive, as was her brother. I read The Road from Home by David Kherdian over and over, book-reported it in English class, told anyone who would listen that I was half Armenian. Looking back, I label myself “obsessed.” In 9th grade, I wrote an abbreviated history, complete with choice gory details, for an extracurricular publication. It drew heavily on a hardback book with a blue cover called The Armenians (I think)–a sweeping history that chronicled the horrors of the genocide. My goal was to shock readers and inspire guilt. It was amateur stuff, fueled by the fire of teenage understanding and the desire to be recognized as something deserving of recognition. My identity was the peg. I’m still glad I wrote about it. I would write it differently today, of course. I’m older. My relationship with my Armenian identity has changed from one marked by pride to one marked by unease.

If you do the math, I am fractionally Armenian–there’s also some Assyrian in there. Every time I try to come up with the actual fraction, I get a headache. “Half” is the default, but it’s probably closer to 3/8. Ethnically, I can claim this Armenian identity. Culturally, this claim rings blatantly false. The last thing my family has are memories and a few recipes we trot out during holidays. Our food is freaking delicious, by the way. We consider Armenian restaurants inferior. They don’t work from Nana’s (Vartouhi’s) recipes, which were kept in her head until the 80’s when a cousin and my mother tried to transcribe what, exactly, “this much” measured in the pinch of her fingers meant.

So we don’t use recipes, really. We use what’s in our heads. Each grandchild took responsibility for one dish. One year someone joked that we should consider sharing what has become compartmentalized knowledge & expertise among ourselves. We should probably take this seriously. An Easter without Choereg is no Easter at all, and I don’t even like Choereg. As my generation scatters, the branches of our family unite less frequently. As we Americanize, we share a love for the family food and identify as eaters, but that seems to be the extent of our heritage. Who are we? There are few left who truly remember.

Some of my relatives are still angry. It’s personal. An affront to our family. I used to have this anger, but it has waned. It’s become less personal for me–I didn’t have as much time with the people the genocide affected directly. As the years pass and my experiences with my relatives slip farther from the present, it’s easier for me to think about larger contexts. I’m not sure how I feel about my ability to detach. Certainly I lament my removal from those I love, from the immediacy of experience and into the fading haze of memory.

It’s not my place to forgive.

Thanks so much for this. I was also more than disappointed by Obama’s refusal to use the word “genocide.” As an African-American (with an Afro-Caribbean mother) who grew up in predominantly white settings, I was also surprised how much your alienation resonated with me. We like to call ourselves a “nation of immigrants,” but I think that really means a nation of people who have been encouraged/pressured/threatened/forced to trade our cultural histories for our citizenship. Though the historical events are different, I have felt that same longing for heritage and cultural identity coupled with the fear of being considered an imposter if I try to embrace it. I think it’s a very American disease, for which I’ve determined the only cure is to embrace my identity. We each get to name our own identity, whether others think we’re “legit” or not. Recently have I begun to say “I’m an Afro-Caribbean. I come from that diaspora. I claim that as my heritage.” Slowly, with trepidation, I’m beginning to search and read and learn as much as I can what that means. This is hard, scary stuff. But maybe it’s no accident that anthropology appealed to you (as it did to me, though my broader field was rhetoric)? Ive come to believe that to take on a culture means taking on its history, and, man, is history personal. But you’ve tapped into a rich vein, and though you may feel like an outsider, you don’t sound like one to me. I could feel in my bones what you wrote here. Thanks again.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Love this; so well put. I’m struck by the fact that our disparate experiences share a common link in their ambivalence, and it meant so much that my specific experience made someone else with their own specific experience feel something. Recognition across difference is so powerful.

History is indeed personal–we can only see it through our own specific lens. That fraught tension between identity, performance, social perception, and one’s own idea of what others’ perceptions are of you…the premium placed upon poorly defined “authenticity”–I like your solution, to embrace what you are in all your complexity. That seems to get to the essence of authenticity: an acknowledgment of your multifaceted truth. Thank you for sharing your thoughts and experiences.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Reblogged this on Dark, On the Prairie and commented:

This is not only a timely reminder of the anniversary of the Armenian Genocide but a profound exploration of how complicated identity can become in American culture.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think I can relate to a lot of what you’ve written. I was born and raised in California as well, though in the north. My father and his family are Palestinian and were dispossessed of their home in Galilee in 1948, and grew up refugees in Lebanon. Although they thankfully did not have to witness their own family killed (at least as far as I know) they lived through a lot of political and social turmoil and had to work hard to rise out of the camps and attain success in their lives.

As a kid growing up in a comfortable home in the US, I never had to worry about the kinds of problems my father, my aunts and uncles, or my grandparents had to face. Of course, I’m happy about that, and I know my father worked hard so that I could have a good life. But there is a gulf between us in that sense – my father lived the effects of being a refugee, a member of a nation without a state, and I haven’t. I even have cousins around my age who have faced restrictions upon their travel based purely on their birth, while as an American, I can travel, work, and live pretty much anywhere I want.

So even though I identify with my Palestinian family and background pretty closely, I also know that I’ve never had to face the hardships they did because of their backgrounds, and I’ve had similar thoughts about being a “phony”. All I can say is that we can’t control the circumstances we’re born into, but I do think I can understand how you feel.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thank you so much for sharing this, and for drawing attention to the generational gulf. Not being able to connect with one’s family is so painful, but when you haven’t shared their struggle, didn’t experience their horrors, it’s impossible. I doubt that family members who have experienced such hardship would want their progeny to know it/experience it–but that shield of ignorance still leaves that distance that you describe so well. Distance that often transmutes into a lack of “culture-cred.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very engaging post- and an interesting take on your heritage; something I must say I can somewhat identify with. I am half Irish and half Chinese, however have not lived in either countries (nor speak either languages at the moment), meaning that, although ethnically speaking, I am both, culturally speaking, I am neither.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Great reflection, even if you feel like you are loosing that heritage, you should try to get it back. You are still Armenian, and you are proud of it. Your post leaves me thinking of human kind and the bad we are capable of doing, but also the good when we put our minds to it.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Being an American means we accept each other for our cultural differences and embrace all of them.I embrace that you have a wonderful Armenian heritage! I too have a similar background and have felt the “phoney me” experience. My mother had told us that her father would joke that his mother ran back to the tribe. I asked her what she meant and she said, supposedly we’re part American Indian. I found out through genealogy research much later, my G. Grandmother and G. Grandfather were on the same reservation. My own mother scoffed with disbelief when I told her and said…”no we’re not”. She came around and kindof is ashamed.

People were protective and afraid to “come out” with what they were for fear of persecution, even in the United States. You would be socially ostracized in 1884 for saying “yeah, I’m a half-breed”. So enjoy being Armenian and be proud of it! I’m going to get the DNA test to prove what I am. Already, I know my B + blood is somewhat rare and found mainly in Asian bloodlines. I’m Indian, Irish, Welsh, uh Italian….and I guess that makes me “American pie”. I’ll celebrate any gosh darn festival, heritage bearing march I damn, well please.

At least you know a few recipes, some cultural stories….the Kardashian girls don’t seem to have a clue. Reach out to them and help them out?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting, even from Australia 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nice post. You did a fantastic job. I started a new blog a week ago, Real Life Natural Wife. I hope you’ll come by and let me know what you think. Have a great weekend!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know the feeling and I still struggle to come to terms even though my heritage is written all over my face!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Pingback: 1915: Thoughts on Armenian Identity from a 4th-Generation Outsider - OverwHelMing

What a powerful, sad and stoic article. Thank you for bearing your heart about your people. Great writing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

There is one thing that ties all the Armenian people together. Although you may never recognize it unless someone tells you, because of your Armenian heritage you carry a

bone-deep sense of grief which you have probably never really understood. My guess is that it’s the racial memory of such a profound level of grief that it will probably take the biblical seven generations to dissipate at all. I did my masters degree on the grandchildren of genocide and Diaspora victims. The result was incredible. We all discovered that we shared this experience of grief and most of us never had had any knowledge of why. Like many veterans, the survivors of such things generally don’t talk about them, leaving subsequent generations mentally free but emotionally distressed without explanation. I’m curious if you had the same experience. Also in case you’re not already aware of it. One of the Ivy League universities in United States was working on a research project with Turkish people to prove that the Armenian genocide was fiction. At the time I was younger and not particularly politically involved but I do remember that there was one senator with an Armenian heritage we stopped them. Of course the United States Placed such a high value on their airbases in turkey that’s sacrificing the truth and defense of our democracy was not too high a price to pay. Say that three times fast and ask yourself if you understand it. It’s interesting also to note as a half Armenian son of an Armenian fatherI have always responded Armenian when I asked my heritage. This much to my grandparents on my mother side distress who are children of the American Revolution. The something about being Armenian thats just more real. Don’t feel hesitant about claiming membership, you are the descendent of Armenians.

LikeLike

As a 4th generation Armenian born in Canada, I understand the sentiment you write about here. However one major difference is in the way I interpret your ethnic authenticity. All you described legitimately makes you Armenian-American. No card-carrying is required. All peoples of the world have varying levels of cultural identity and pride coursing through them. Whatever you are makes you your own brand of Armenian. And for the record Assyrian as well. I like to say I’m of Armenian descent with influences from Ethiopia (where 2 generations of my family hail from), Greece (maternal grandmother is from there), and Canada (where I am born/bred/currently reside). That’s my own brand of being Armenian. Integration to the local community is part of the Armenian identity. So in my eyes, you are an authentic Armenian 🙂 playing backgammon in the parks of Glendale is optional 😉

LikeLike

I can relate to a lot of this even though I am only half generation (is there such a thing?), especially on the “authenticity” point. Very moving post. I find this place of unease much more interesting, personally.

LikeLike

Thanks for writing this very interesting article, I shared it with David Kherdian. Root River Return, his new book, is about his youth, growing up in an Armenian American community in Racine, Wisconsin in the 1930’s and 40’s. Best regards.

LikeLike

I read ‘Armenian Golgotha’ by Grigoris Balakian several years ago and was stunned. It was the first time I’d ever heard of the Armenian atrocity. I’d read many books about the Jewish holocaust, Rwanda, Darfur, Bosnia, and of course the Native Americans in our own country. I know there have been many other occasions but the particular experience of the Armenian people seemed to be a very well kept secret! I’m glad you’re sharing your families experiences and remembering their history. We should keep the past ever before us, being certain not to repeat it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for this, Rachel. Beautiful writing that I will share with my friend Linda Margarian who lives in La Canada and has expressed some of the same sentiments.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m very glad you reposted this. Alice will grow up hearing the stories because you will share them. That is why we share, and should continue to do so.

LikeLiked by 1 person